From “The Requirements Document” to “The Conversation”

Early in my career, I thought the job of a product manager was to write perfect specifications. I would spend days crafting 30-page documents, detailing every edge case and error state. I would hand these over to engineering with a sense of pride.

Then I would watch in horror as they built something completely different.

The problem wasn’t that I hadn’t written enough. It was that I had written too much, and talked too little.

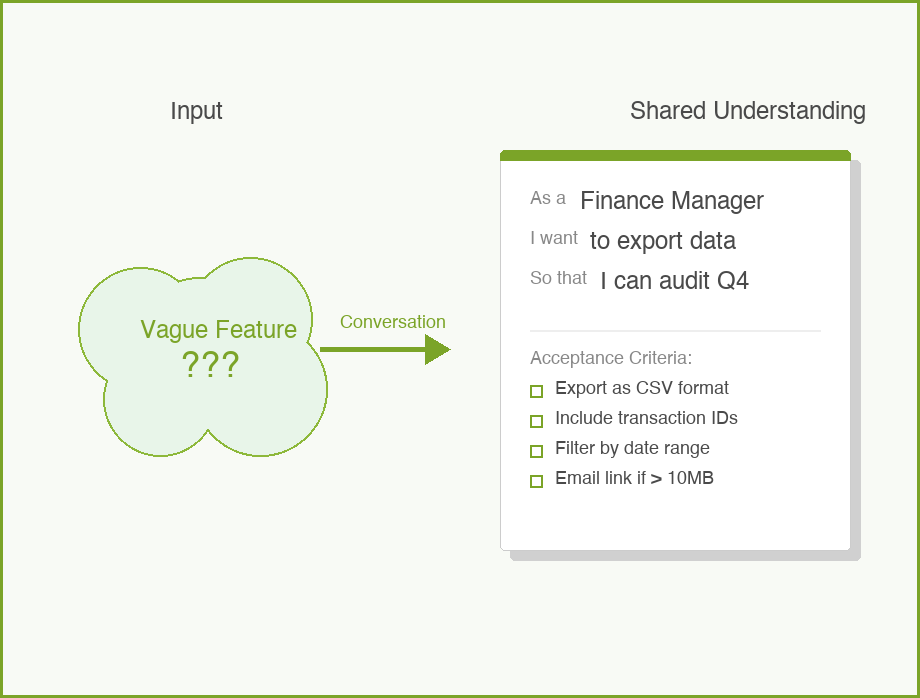

This is where User Stories come in. They are deceptively simple, but they are one of the most powerful tools in the Product phase of the 5Ps. When done right, they shift the focus from writing requirements to building shared understanding.

What is a User Story?

A user story is a short, simple description of a feature told from the perspective of the person who desires the new capability, usually a user or customer of the system.

But here is the important part: a user story is not a specification. It is a placeholder for a conversation.

Ron Jeffries, one of the creators of Extreme Programming, described the three Cs of a user story:

- Card: A physical index card (or Jira ticket) that contains the story text. It is small for a reason—it limits how much you can write.

- Conversation: The discussion between the PM, the designer, and the engineer to flesh out the details. This is where the real work happens.

- Confirmation: The acceptance criteria that confirm the story is done correctly.

If you are just writing tickets and throwing them over the wall to engineering, you are missing the point.

The Standard Formula

Most teams use a standard template:

As a [type of user], I want [some goal] so that [some reason].

It looks rigid, but it forces you to answer three critical questions:

- Who are we building this for? (It is rarely just “a user”).

- What are they trying to do?

- Why does it matter?

In my experience, the “Why” (the so that clause) is the most critical part. It gives the engineering team context. If they know why a user wants a feature, they can often suggest a better, cheaper, or faster way to solve the problem than what you originally thought of.

Common Mistakes

I have written thousands of user stories. Here are the mistakes I see most often (and have made myself):

1. The Generic User

“As a user, I want…”

Who is this user? Is it a first-time visitor? An admin? A frustrated customer trying to cancel? “User” is lazy. Be specific. “As a Finance Manager” or “As a New Subscriber” changes how the team thinks about the solution.

2. The Technical Task in Disguise

“As a developer, I want to upgrade the database so that the system is faster.”

This might be a necessary task, but it is not a user story. A user story must deliver value to a human. If you need to do technical work, just call it a “Task” or “Chore.” Don’t force it into the user story format.

3. Missing the “So That”

“As a customer, I want to download my transaction history.”

Why? To file taxes? To check for fraud? To import it into Excel?

- If it is for taxes, maybe a PDF summary is better.

- If it is for Excel, a CSV is better.

Without the “so that,” you are asking your team to guess.

A Concrete Example

Let’s look at a bad example and fix it. Imagine we are building a banking app called “BankRight”.

Bad:

As a user, I want to reset my password.

Better:

As a forgetful account holder, I want to reset my password via a magic link sent to my email so that I can regain access without remembering security questions.

Notice the difference? The second one tells us who (someone who forgot), how (magic link, implying a specific solution direction), and why (avoiding the friction of security questions).

The INVEST Criteria

When I am reviewing stories for BankRight, I use the INVEST mnemonic to check if they are ready for development. I didn’t invent this (Bill Wake did), but I use it all the time.

- Independent: Can this be built and deployed by itself?

- Negotiable: Is there room for discussion? (Remember: it’s a conversation).

- Valuable: Does it provide value to the customer?

- Estimable: Is it clear enough for engineers to guess how long it will take?

- Small: Can it be done in a few days? If it takes two weeks, it’s too big. Break it down.

- Testable: How will we know it works?

Acceptance Criteria: The Guardrails

While the story itself describes the intent, the Acceptance Criteria (AC) describe the constraints. This is where you get specific.

For our BankRight password reset story, the AC might look like:

- Link expires after 15 minutes.

- Link can only be used once.

- User receives a confirmation email after the change.

- Old password cannot be reused.

I try to write these as a checklist. It makes it easy for the QA team (and the developer) to verify their work.

How to Use With AI

Writing user stories is one of the best use cases for Generative AI. It excels at structure, variation, and edge case detection. But remember: AI is the facilitator, not the decision maker. You own the context.

Here is how I use AI to speed up my user story writing process:

1. Draft the First Pass

Don’t start from a blank screen. Paste your raw notes or a transcript of a stakeholder meeting and ask the AI to draft stories.

Prompt:

“I am a PM for a banking app. We are building a feature to let users freeze their debit cards instantly. Based on these meeting notes, draft 5 user stories in the standard format (As a… I want… So that…).”

2. Generate Acceptance Criteria

This is where AI saves me hours. It often thinks of negative paths I might miss.

Prompt:

“Here is a user story: ‘As a cardholder, I want to freeze my card so that no new transactions are approved.’ List 10 acceptance criteria for this story. Include happy path, error states, and security considerations.”

3. Split Large Stories

If a story feels too big (it fails the “Small” in INVEST), ask AI to break it down.

Prompt:

“This user story seems too large for a single sprint: ‘As an admin, I want to manage all user permissions.’ Split this into 3-5 smaller, independent vertical slices that still deliver value.”

The Guardrail

Always review the output. AI tends to be generic (“As a user…”). You must enforce specificity (“As a Fraud Analyst…”). Also, AI will not know your technical constraints unless you tell it. If you can’t build magic links yet, don’t let the AI put it in the story.

Conclusion

Writing great user stories is a craft. It takes practice to balance brevity with clarity. But remember: the goal isn’t to write the perfect sentence. The goal is to create a shared understanding so your team can build the right thing.

Start with the conversation. The ticket is just the receipt.

What about you? How does your team handle requirements? Do you use the standard format or something else? Comments are gladly welcome.