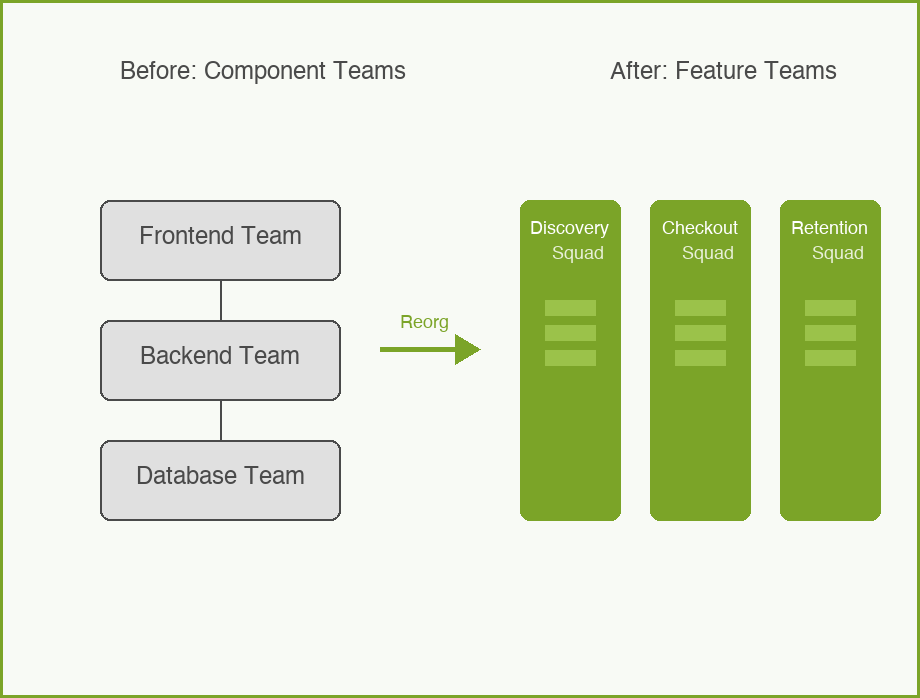

From “Silos” to “Squads”

You can hire the best engineers in the world. You can recruit the smartest product managers. You can buy the most expensive tools. But if your team structure is flawed, you will still move at a glacial pace.

I have seen this pattern repeat in startups and enterprises alike. The symptoms are always the same: meetings multiply, decisions stall, and shipping even a simple feature feels like pulling teeth. The problem isn’t the people. It is the structure.

There is a famous observation called Conway’s Law, which states that organizations design systems that mirror their own communication structure. If you have a database team, a backend team, and a frontend team, you will inevitably build a product that is stitched together from three separate pieces. And every time you want to release a new feature, you will need a meeting with all three teams to coordinate.

In the 5Ps framework, team structure sits in the Platform phase. It is the foundation that allows—or prevents—your teams from doing their best work.

Two Common Models

There are many ways to organize product teams, but most fall into two main categories. Marty Cagan of SVPG famously distinguishes between “feature teams” and “component teams.”

Component Teams

This is the traditional IT approach. You group people by their technical skill or architectural layer. You have a “Mobile Team” (iOS/Android engineers), a “Backend Team” (Java/Go engineers), and a “QA Team.”

On paper, this looks efficient. The mobile engineers sit together and learn from each other. The backend architecture stays clean because one team owns it.

But in practice, it is a nightmare for speed. To ship even a simple feature—like adding a “Save to Wishlist” button—you need the Mobile Team to build the UI, the Backend Team to update the API, and the Database Team to modify the schema. If one team is busy, the whole feature waits.

Feature Teams

This is the modern product approach. You group people by the customer problem they are solving or the business outcome they are driving.

A “Search Team” might include a product manager, a designer, two backend engineers, one frontend engineer, and a data scientist. They have everything they need to build, ship, and measure search features. They don’t need to ask permission from another team to change the database schema for their search index.

A Concrete Example: ShopRight

To make the discussion more concrete, let’s look at a hypothetical e-commerce company called “ShopRight.”

The Old Way (Component Teams)

ShopRight started with a classic structure:

- Web Team: Owned the website.

- App Team: Owned the iOS and Android apps.

- Platform Team: Owned the APIs and database.

When the Head of Product wanted to launch a “Buy Online, Pick Up in Store” feature, it was a disaster. The Web Team built the interface in two weeks. But the Platform Team was backed up with technical debt work and couldn’t touch the API for a month. The App Team realized halfway through that they needed a different API endpoint than the Web Team.

The project took six months. By the time it launched, a competitor had already captured the market.

The New Way (Feature Teams)

ShopRight reorganized into “Squads” based on the customer journey:

- Discovery Squad: Focused on helping users find products (Search, Browse, Recommendations).

- Conversion Squad: Focused on the transaction (Cart, Checkout, Payments).

- Retention Squad: Focused on bringing users back (Loyalty, Wishlist, Notifications).

Now, let’s look at that same “Buy Online, Pick Up in Store” feature. It falls clearly under the Conversion Squad. This team has its own backend engineers and mobile engineers. They sat down, designed the API changes they needed, updated the app and website, and shipped the first version in three weeks.

They didn’t have to wait for the “Platform Team.” They were the team.

Team Topologies

While “Feature vs. Component” is a great starting point, the reality is often more complex. You can’t just have feature teams; otherwise, who maintains the shared infrastructure?

This is where the work of Matthew Skelton and Manuel Pais in Team Topologies is incredibly useful. They identify four fundamental team types:

- Stream-aligned teams: These are your feature teams. They align to a stream of work (like a customer journey) and deliver value directly.

- Enabling teams: Specialists who help stream-aligned teams acquire missing capabilities (e.g., an accessibility expert who rotates between teams).

- Complicated-subsystem teams: Teams that manage highly specialized technical components (e.g., a video processing engine or a face recognition algorithm) that require deep expertise.

- Platform teams: Teams that provide internal services (like a deployment pipeline or a design system) to reduce the cognitive load on stream-aligned teams.

This nuance is critical. You want most of your teams to be stream-aligned, but you support them with a strong platform team so they don’t have to reinvent the wheel.

How to Choose

So, which structure is right for you?

If your goal is technical consistency and resource efficiency, component teams often win. It is cheaper to have one pool of DBAs than to embed a database expert in every squad.

But if your goal is speed of delivery and customer value, feature teams are superior. The cost is redundancy—you might have two teams solving similar problems—but the benefit is autonomy.

In my experience, startups should almost always use feature teams. Speed is your only advantage. As you scale, you will need to layer in platform teams to keep the chaos in check, but the core unit of delivery should remain the cross-functional squad.

How to Use With AI

Reorganizing a team is a sensitive human process, but AI can be a powerful tool for analyzing your structural logic before you move a single desk.

1. The “Conway’s Law” Detector If you aren’t sure where your current structure is broken, paste a month’s worth of “blockers” from your status reports into an LLM.

- Prompt: “Here is a list of reported blockers from our last 4 weeks of status updates. Analyze these to identify patterns of dependency. Which teams are most frequently waiting on other teams? Based on this, suggest which components might need to be moved into the blocked team’s ownership to increase autonomy.”

2. Stress-Testing Team Topologies When drafting new team boundaries, you can use AI to simulate the “cognitive load” on a proposed team—a key concept from Team Topologies.

- Prompt: “I am designing a new ‘Checkout Squad’ that will own the cart, payment processing, and post-purchase email flows. Act as a devil’s advocate using the principles of Team Topologies. Is this scope too broad for one team (too high cognitive load)? Or is it appropriate? Identify potential fracture points.”

Guardrail: AI sees logic, not relationships. It might suggest a mathematically perfect structure that fails because two key leaders hate each other. Use AI to check the theoretical soundness of your model, but make the final decisions based on your knowledge of the people involved.

Conclusion

Changing team structure is painful. It disrupts relationships and changes reporting lines. But it is also one of the highest-leverage changes you can make as a leader.

If your team feels slow, don’t just ask them to work harder. Look at your org chart. Are you structured to ship value, or are you structured to ship code components? The difference is everything.

What do you think? Have you seen a transformation from component to feature teams work well (or fail)? Comments are gladly welcome.