From “Wall of Text” to “Blueprint for Success”

In my career, I’ve seen two types of PRDs. The first is a 40-page “Requirement Bible” that took three months to write and was obsolete the day it was finished. The second is a vague one-pager that says “Make it pop.” Neither works.

The trick isn’t to write more; it’s to write the right things for your specific context. A B2C mobile app needs a completely different definition of success than a backend data pipeline.

In this article, I provide a comprehensive list of PRD sections, and then curate specific templates for four common use cases: B2B Enterprise, B2C Consumer, Data Infrastructure, and AI Infrastructure.

What is a PRD Template?

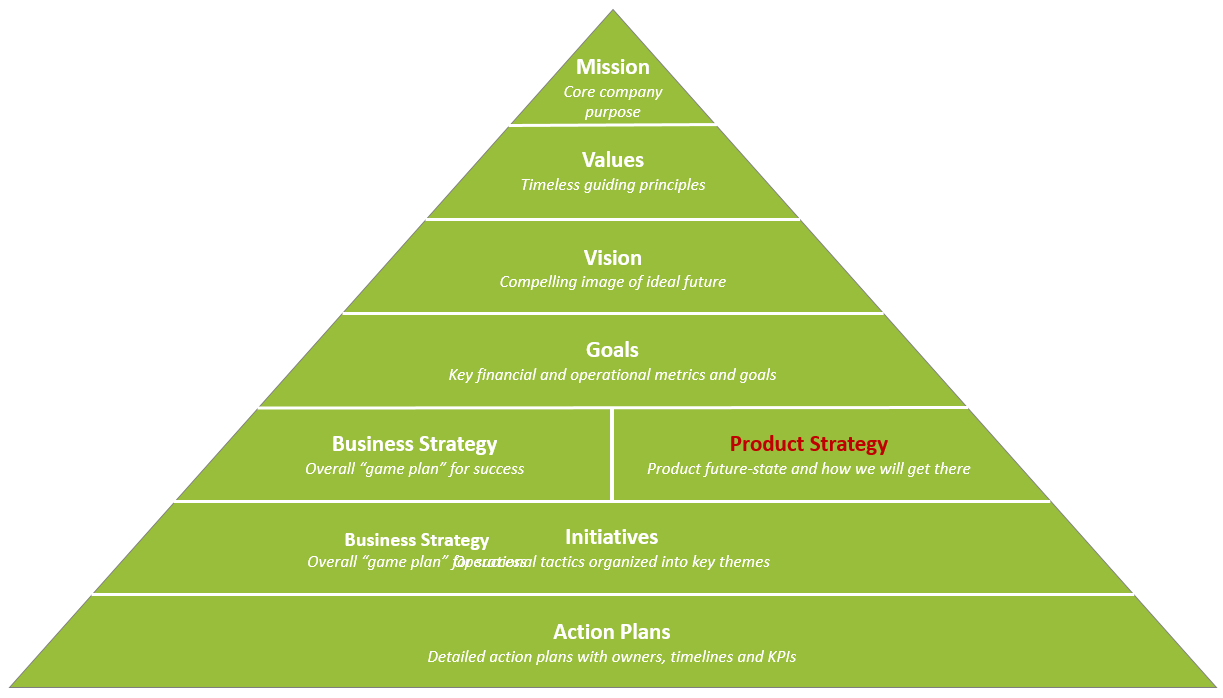

A Product Requirements Document (PRD) template is just a checklist to ensure you haven’t forgotten anything critical. It is the container for your strategy. It aligns stakeholders, communicates vision, and provides a clear roadmap for engineering.

But remember: The template is not the product. Filling out every section of a template doesn’t guarantee a good product. Use these templates as a starting point, not a straightjacket.

1. B2B Enterprise (The “Heavy Lifter”)

Best for: Complex SaaS, Workflow Tools, Regulated Industries

This format is designed for products where “the buyer is not the user.” It separates the Problem Space (why we are doing this) from the Solution Space (what we are building) to prevent jumping to conclusions.

Key Characteristic: Heavy emphasis on Business Logic, Permissions, and Integrations.

Format: The Enterprise PRD

Overview

- Document Control: Product name, author, version, status, stakeholders.

- Executive Summary: High-level overview of purpose and strategic context.

- Background & Scope: Why now? What is in/out of scope?

Problem Space

- Customer Segments: Who are we solving for? (Buyer vs User personas).

- User Personas: Detailed profiles of the target users (Goals, Frustrations, Behaviors).

- Problem: Detailed articulation of the top 3 problems, ranked by severity.

- Impact Analysis: What is the cost of inaction? (Revenue loss, churn risk).

- Existing Alternatives: How do they hack this together today?

Solution Space

- Unique Value Proposition: The “Hook” – why is this different?

- Solution Features: Top features mapped directly to the problems above.

- User Stories: Functional requirements in story format (“As a [user], I want…”).

- UX/Design Requirements: Wireframes, complex flows, state diagrams.

- Technical Requirements: Security, compliance (SOC2/GDPR), integrations.

- Unfair Advantage: What makes this defensible?

Go-to-Market

- Channels: Sales enablement, partner channels.

- Revenue Model: Pricing strategy (per seat, per usage).

- Cost Structure: CAC, implementation costs.

Execution

- Key Metrics: Adoption, retention, ACV impact.

- Project Planning: Milestones, dependencies, risks.

2. B2C Consumer (The “Growth Engine”)

Best for: Mobile Apps, Social Networks, D2C Subscriptions

In consumer products, utility is often less important than psychology and habit formation. Users don’t “have” to use your product; they have to want to. This template focuses less on functional requirements and more on the user journey and growth loops.

Key Characteristic: Heavy emphasis on User Psychology, Virality, and Experimentation.

Format: The B2C PRD

Core Experience

- Target Audience & Personas: Who is the primary user? What is their archetype?

- The “Hook”: What is the single trigger that gets a user to try this?

- Emotional Goal: How should the user feel after using this? (e.g., “Smart,” “Connected,” “Relieved”).

- User Stories / Job Stories: Key scenarios (“When [situation], I want to [action], so I can [outcome]”).

- The Core Loop: Trigger → Action → Reward → Investment. (Reference: Nir Eyal’s Hooked).

Growth & Virality

- Acquisition Channel: Organic search, paid ads, referral?

- Viral Mechanism: How does one user bring in the next? (e.g., “Invite to collaborate,” “Share content”).

- Monetization Moment: Where is the friction introduced? (Paywall, Ad).

UX & Design (Critical)

- Visuals: High-fidelity mockups are mandatory here. Text is insufficient.

- Micro-interactions: Delightful animations or feedback loops.

- Onboarding Flow: Step-by-step breakdown of TTTV (Time to Target Value).

Experimentation

- Hypothesis: “We believe that X will result in Y.”

- A/B Test Variants: Variant A (Control) vs Variant B.

- Success Criteria: Specific conversion rates (e.g., “Day 1 Retention > 40%”).

3. Data Infrastructure (The “Plumbing”)

Best for: APIs, Data Pipelines, Platform Migrations

Here, there are no “users” in the traditional sense. The “user” is another system or a developer. This PRD is technical, precise, and unforgiving. Ambiguity here causes outages.

Key Characteristic: Heavy emphasis on SLAs, Schemas, and Migration Plans.

Format: The Data Infra PRD

Contract & Schema

- Consumer Personas: Who are the downstream users? (e.g., Data Scientists, Dashboard Owners).

- Data Dictionary: Exact field names, types, and definitions.

- API Spec: Endpoints, request/response bodies (OpenAPI/Swagger link).

- Usage Scenarios / Stories: Key access patterns and query types supported.

- Data Freshness: Real-time vs. Batch? What is the maximum acceptable lag?

Service Level Agreements (SLAs)

- Availability: 99.9% vs 99.99%?

- Latency: p95 and p99 requirements.

- Throughput: Events per second (EPS) expectations (Peak vs Average).

Consumers & Dependency

- Downstream Consumers: Who breaks if this changes?

- Upstream Dependencies: What source systems do we rely on?

- Versioning Strategy: How do we handle breaking changes?

Migration Plan

- Backfill Strategy: How do we move historical data?

- Cutover Plan: Dual-write period? Hard cutover?

- Rollback Plan: “Break glass” procedure if data is corrupted.

4. AI Infrastructure (The “Brain”)

Best for: LLM Features, Recommendation Engines, Chatbots

AI products are probabilistic, not deterministic. You cannot write a requirement like “The model must answer correctly 100% of the time.” This template focuses on evaluation and guardrails.

Key Characteristic: Heavy emphasis on Evaluation (Evals), Context, and Safety.

Format: The AI Infra PRD

The Job to Be Done

- User Personas: Who interacts with the model? (e.g., End User vs Admin).

- User Intent: What is the user trying to achieve? (e.g., “Summarize text,” “Generate code”).

- Interaction Stories: Key prompts and expected model behaviors.

- Model Selection: Build vs Buy? (GPT-4, Claude, Llama, custom fine-tune?). Why?

Data Strategy

- Context Window: What data creates the prompt? (RAG strategy).

- Training/Fine-tuning Data: Source, cleanliness, and bias checks.

- Feedback Loop: How does user feedback (thumbs up/down) improve the model?

Evaluation Framework (The most important part)

- Golden Dataset: The “Test Set” of 50-100 examples we trust.

- Success Metrics:

- Quantitative: Latency, Tokens per second, Cost per query.

- Qualitative: “Helpfulness,” “Factuality” (measured by human review or LLM-as-a-judge).

- Acceptance Threshold: “Must be better than current baseline on 80% of Golden Set.”

Safety & Guardrails

- Refusals: What should the model refuse to do?

- Hallucination Mitigation: How do we ground the answers?

- Privacy: PII handling and data retention.

5. PRD Section Buffet (The “Kitchen Sink”)

This comprehensive format combines all unique sections from every PRD template. Use this as a menu to cherry-pick what you need.

All Sections

- Document Control: Product/feature name, author, version, status, last updated, key stakeholders

- Overview & Context: Executive summary, strategic context, background/history, scope (in/out)

- Problem Space: Problem definition, user pain points, impact analysis, market gaps, business case

- Target Users: Personas, use cases, user journey maps, underserved needs

- Solution: Product vision, value proposition, differentiators, alternatives rejected

- Features & Requirements: Prioritized feature list (MoSCoW), user stories, acceptance criteria, MVP set

- Technical Requirements: Architecture, performance specs, security, integration points, API contracts

- UX/Design Requirements: Wireframes, mockups, user flows, design constraints

- Go-to-Market: Launch strategy, release phases, channels, support requirements

- Success Metrics: KPIs, pirate metrics (AARRR), measurement plan

- Business Model: Revenue streams, pricing, cost structure, unfair advantage

- Project Planning: Timeline, milestones, resource requirements, dependencies

- Risk Management: Risk assessment, mitigation strategies, open questions

- AI Specifics: Model selection, evaluation set, prompt strategy, safety guardrails

Deep Dive: The Living Document

A PRD is not a statue; it’s a living organism. The biggest mistake I see is teams treating the PRD as “Done” once development starts.

The PRD should be the Single Source of Truth (SSOT). When requirements change (and they will), update the PRD. If you make a trade-off decision in a Slack thread, copy it back to the PRD. If the PRD drifts from reality, it becomes useless trash.

Pro Tip: Add a “Decision Log” section at the bottom of your PRD to track why changes were made during development.

Why This Matters

Standardizing your PRD structure (or at least having a thoughtful one) reduces cognitive load.

- Speed: Stakeholders know exactly where to look for “Success Metrics” or “Risks.”

- Completeness: You won’t wake up 2 days before launch realizing you forgot to define the “Error States.”

- Alignment: It forces the hard conversations early, when they are cheap to fix, rather than in code, when they are expensive.

How to Use With AI

AI is the world’s best PRD drafter. It removes the “Blank Page Syndrome.” But you must drive it.

Pro Tip: Store your chosen PRD template as a markdown file (e.g., prd_template.md) in a context/ or docs/ folder within your code repository. This keeps your requirements version-controlled alongside your code and makes it easy for engineers to reference the “Single Source of Truth” without leaving their IDE.

- Drafting: Don’t say “Write a PRD.”

- Prompt: “Act as a Senior Product Manager. I am building a [B2C Fitness App] for [Busy Parents]. Based on the transcript of my user interviews below, draft the ‘Problem Space’ and ‘User Personas’ sections of the PRD. Focus on psychological triggers.”

- Critique: Use AI as a hostile stakeholder.

- Prompt: “Act as a cynical Engineering Lead. Review this ‘Solution’ section for technical feasibility and edge cases. What am I missing? What is too vague?”

- Expansion: generating edge cases.

- Prompt: “List 10 potential error states or ‘unhappy paths’ for this user flow that I should account for.”

Guardrail: Never let AI define your Strategy or Success Metrics. Those require human judgment and accountability.

Conclusion

There is no “Perfect PRD.” The best PRD is the one that gets your team to build the right product with the least amount of friction.

If you are a 3-person startup, a bulleted list in Notion is fine. If you are building a banking platform, you better have that Data Infra template locked down.

Pick the template that fits your stage, your user, and your risk profile. And then, get to work.

What templates does your team use? Do you have a specific “AI” section yet? Comments are gladly welcome.